The Altar Within Newsletter —notes on life, magic, and liberation. (Exclusive offerings for paid subscribers: learn more here )

PRE-ORDER my forthcoming book: THE ALTAR WITHIN - A Devotional Guide To Liberation (2nd Edition) —Pre-Order HERE

Tomorrow, March 13th, is my 44th birthday.

My birthdays are always a blur to me—maybe because I tend to check out. In the days leading up to my birthday, I start to feel sad, anxious, and numb. And when the day finally arrives, all I want is to disappear into a dark hole where no one can reach me, see me, or celebrate me. Why?

If you’ve read my books and have been with me long enough to catch glimpses of my past—on the rare occasions I open up—you know that I had what some might call an unfortunate childhood.

My parents immigrated to the United States at the end of 1980, part of what history calls Los Marielitos.

—Marielitos is the name given to the Cuban immigrants that left Cuba from the Port of Mariel in 1980. Approximately 135,000 people left the country to the United States from April to September in what became known as the Mariel boatlift.

On those boat lifts were thousands of people crammed into small boats. My mother, who was four months pregnant with me (I am considered a Marielita), avoids talking about her experience. So it’s a treat when she does open up to me.

One birthday—my 13th, to be exact, my mother decorated our little kitchen with pink balloons, blown up by mouth and taped to the wall beside a letter banner that read Happy Birthday in gold. Below it, a small table covered in plastic, printed with a repeating pattern of cheerful clowns. It’s what was left in the recycled decoration bag we kept in the closet.

The day before, she had bought me a Cuban cake from a nearby bakery—a single-layer cake with white frosting and pink ribbon patterns along the edges. The flavor? Guava, my favorite. Surrounding the cake were pastelitos, empanadas, maduros, bocaditos, and a few bottles of soda.

It was around 8 a.m. when I started to wake up, stretching my arms and legs before sitting up. Through the hum of the furnace heater—whistling as the hot water rushed through its pipes to warm my room, I could faintly hear laughter outside our window. Our window, because I shared a small room with three younger sisters.

My sister Kathy leaped out of bed, ran to the window, and yelled, “SNOW DAY!”

I rubbed my eyes with the backs of my hands and through my hazy sight I could see my sister’s big head of curls swaying and flopping as she danced with excitement.

I threw my sheets off and ran to the window.

Sigh. Snow day.

My mother had planned a big 13th birthday for me, inviting all the kids from the projects (project housing). My sisters and I rushed to the living room, plopping down in front of the big-box TV to watch the news channel announce school closures, one by one.

Washington Middle School, closed.

Emerson High School, closed.

St. Mary’s Middle School, closed.

And after what felt like a hundred more names—

Edison School, closed.

My sisters and little brother erupted in joy, scrambling to throw on their “snow gear,” which meant layers upon layers of clothes and socks. I just sat there, staring at the screen, barely breathing.

Normally, I would have been the happiest kid in the world for a snow day. But I knew—deep in my gut—that this snow day was going to ruin everything.

My mother knelt beside me and said, “No te preocupes, vamos a ver qué pasa.” Don’t worry, let’s see what happens.

By afternoon, the snowfall was so heavy it buried cars and blocked doors halfway up. The phone rang endlessly—one parent after another calling to say they were sorry, but they couldn’t let their child trudge through the storm for my birthday.

I was still in my white pajamas, covered in a Rainbow Brite pattern—her on her horse, Starlight, alongside her friends: Lucky, Champ, Romeo, Spark, OJ, IQ, Hammy, and Twink (my favorite).

I sat at the table, behind the cake, alone. Elbows on the table, chin resting in my fists.

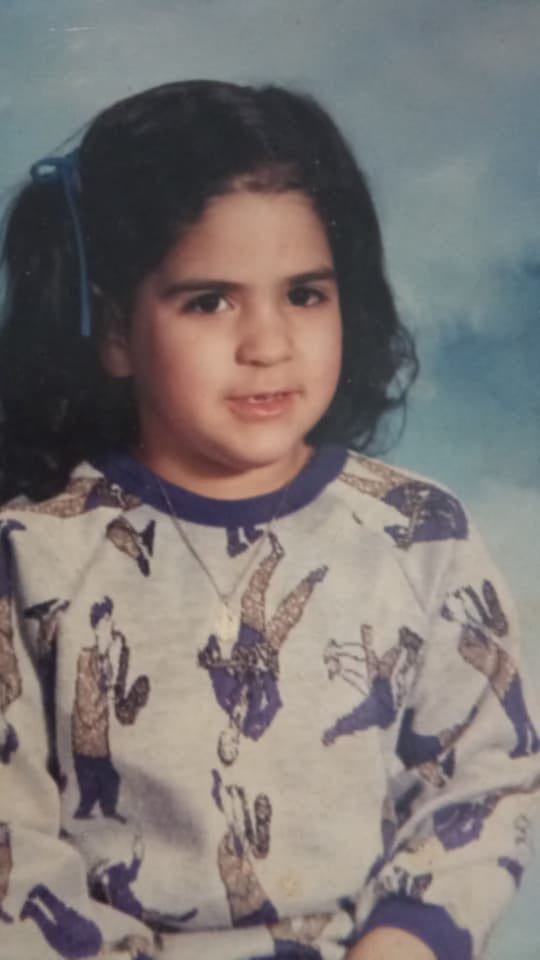

The photo above was taken that night—my 13th birthday at 8 p.m. My mother had forgotten to take any pictures during the day, so she came into the room to snap one before it was over.

Our small room had bunk beds and a single bed. I usually slept on the single, but we rotated so that everyone got a turn. Did you know I hate the color pink? I think it’s because it was forced on me, surrounded by all my girly sisters. I was the tomboy, the sporty one. Those awards on the wall? They were mine—basketball, track, soccer, and dance.

While I sat at the table sulking, my mother walked in, smacked my hands from under my chin, and said, “Hija, deja de ser dramática.” Daughter, stop being dramatic.

She sat down next to me and slid a Materva across the table. I loved that drink. She only bought them for holidays and special occasions. A Cuban soda made with yerba mate, it had a sweet taste and a scent I adored.

“Bueno, want me to tell you a story?” she asked.

My eyes widened, and a smile stretched across my face. I leaned in eagerly. ”¡Sí!”

She knew how much I loved stories—I had been an avid reader from a young age.

“Since it’s your special 13th birthday,” she said, “I’ll share a little about my journey across the ocean on my way here.”

“Leaving my home was heartbreaking. Cuba was in a bad state—your grandparents and aunts were barely making ends meet, and with a baby on the way, I couldn’t let that be your reality. Food was scarce, supplies were low, and the future of Cuba was uncertain. Fidel opened the port, and I took a risk to find a better life for us.

Your father, a freedom fighter, was arrested shortly before the announcement. I learned that many of the prisoners they called criminals were going to be placed on the boats to the U.S. And he was one of them.

She paused, almost as if she felt my my stomach twist when she mentioned my papa.

You know they weren’t criminals, right?” she said, leaning in and wiping icing from the corner of my mouth with her thumb while the rest of her hand held my face.

I snuck a finger full into my mouth from the back corner, hoping she wouldn’t notice.

“They were people like your father, who loved their country and communities so much that they fought for our rights under a regime that was taking our Indigenous lands, claiming ownership of our homes, our farms, even the very crops and food we grew.”

She leaned in closer, staring me straight in the eyes.

“Never believe what comes out of the oppressor’s mouth. They will eat your mind and claim your soul.”

She left me there, mouth slightly open, absorbing her words.

She settled into her chair and sighed. Her eyes glazed over, her cheeks flushed.

“I’ve never seen so much darkness in one place in such a short time. It took about 12 hours to cross the ocean and arrive in Florida. Children and the elderly were starving, and the grief was so thick you could cut it with a knife.

The sharks… so many sharks. They would bump the boat, waiting for their next meal. I can still smell the blood-stained water, the scent of sun-scorched flesh and filth sticking in my throat. Some people didn’t make it—injuries, fights. They were dumped overboard.”

She exhaled sharply.

“I placed my hands on you, on my belly, and prayed the entire way.

You are also the daughter of Yemayá. Water embraces you like a hug from the very ocean itself. Swimming in my belly while journeying across the ocean to lands we didn’t know.

And the alignment of your arrival into the winds in March… my little fish, the daughter of the waters you most definitely are.”

Pisces Sun - Cancer Moon - Libra Rising

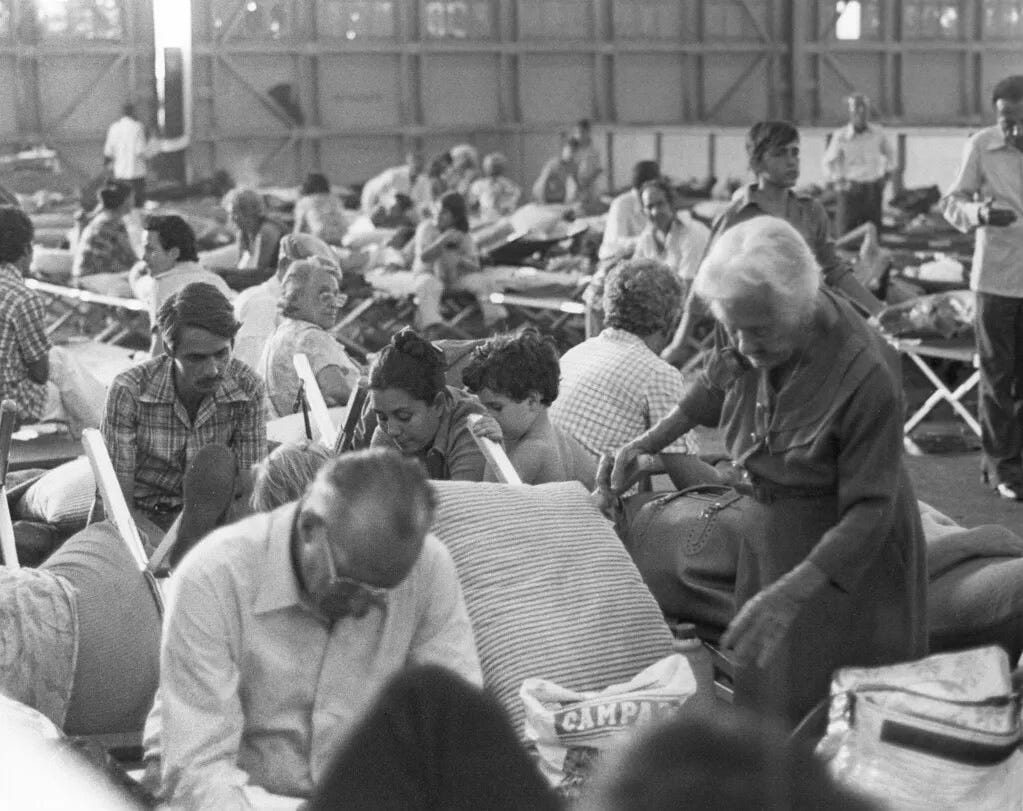

“Once we arrived, I was placed in a refugee camp. That’s when things really got worse. Women were abused and assaulted. Men fought among themselves. But there was good, too.

Despite the grief, hunger, fear, worry, and sleepless nights, people came together. We watched over one another. We did the best we could under the circumstances.

—refugee camp

The long days and nights of waiting—wondering what would happen to us—made everyone on edge. We were reactive, but we were just human beings longing for a chance at a better life, a warm bed, a place to finally call home.”

Tears ran down my mother’s swollen cheeks as she spoke, holding back the darkest details of what she had endured, of what she had witnessed.

You see, my life wasn’t easy. A home filled with alcoholism, drugs, abuse—mental, physical, emotional. Predatory guardians and family friends. Gang violence. Police violence. Poverty. And yet, despite it all, I still have good memories. My mother tried her best. Her love shifted over time, from gentle affection to tough love. But I could never blame her. Not after everything she had been through. Not after everything we had been through.

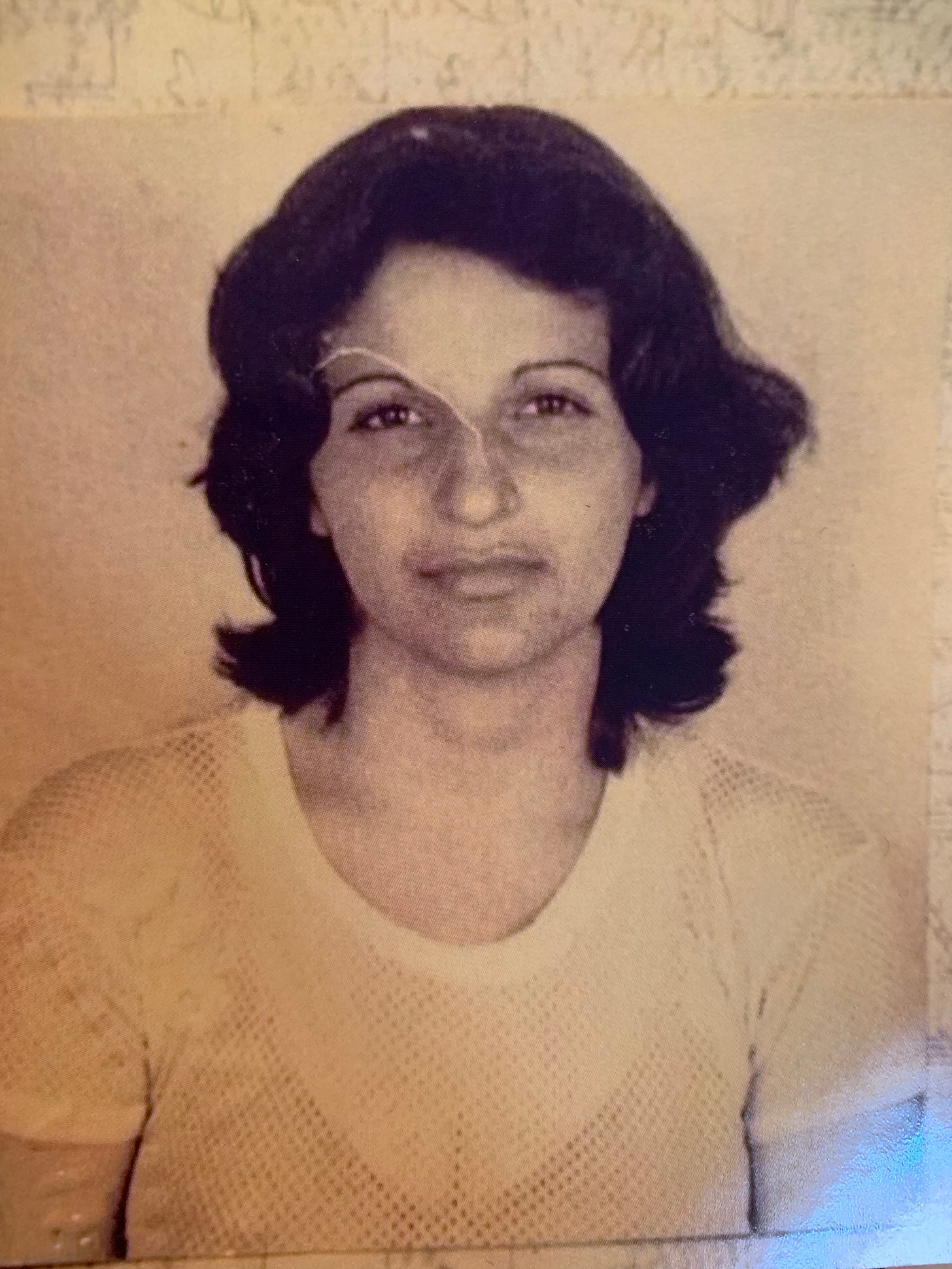

—mi papa

My father, a good man, was torn apart the moment he arrived in this country. His once fiery and loving heart turned cold and weary. Unlike many Cubans who had family already established here, my mother and father were the first to leave our island. A better chance at life meant you had to make money to survive —a lot of it. My parents had left a country where they could barely support themselves for one that promised dreams—only to find that promise was a lie. A trick. A trap.

Not everyone will agree with that statement, and that’s okay. Your experience is not like mine, and vice versa.

My father was murdered when I was five years old. He had become a drug dealer, like many Cubans at the time. It was the only way they could make money to support their families. And before anyone says, he could have just gotten a regular job—could he? Immigrants, especially Cubans, were not wanted in America. No one wanted to hire them. Those who got lucky had family here to help. My father tried to work at a car lot, but the owner paid him so little he could barely afford his own lunch. He took on many jobs, but none of them paid enough to cover rent, put food on the table, or afford even the bare necessities.

Have you watched Griselda on Netflix?

My father became addicted after being forced to try the product himself. Before that, he had never touched drugs. He was never abusive. But once the addiction took hold, everything changed. The warm, joyful man I loved turned into someone else, and my mother and I were constantly on the run to get away from him. He never hurt me, but he hurt my mother.

After four years of that life, of watching his family fall apart, he tried to leave that life behind. Shortly after, he was found under an overpass —shot twice in the head, his body thrown away like garbage.

My papa. My warm bear hug. Mi papi.

I have never healed from seeing my father in that coffin—lifeless, cold to the touch, no soul threads left in his body. My mother thought it was a good idea to let her five-year-old see her father at his funeral. That was the first time I had a panic attack. It would not be the last.

He had promised me. For my fifth birthday, he said, he would be clean. He would come home. I still remember the way he held my little face in his hands, looking into my eyes. “Te lo prometo,” he said. I promise you.

I can still smell the ammonia and gasoline on his breath. — cocaine.

“Por favor, papi, come back home.”

He never made it to my fifth birthday.

And maybe, in some ways, a part of me is still waiting. Still waiting for the scent of sweet yerba mate on his breath, for the day he walks through the door to watch me open the gift he bought me before he died.

A bike.

Green, with sunflowers painted on it. Training wheels. A basket and a small silver bell.

His friend had been holding onto it in his garage, waiting for my father to pick it up. When my birthday came, he brought it over.

I stared at it for a long time. Finally, I got up from the sidewalk and reached out, tracing my fingers over the handles, the frame, the seat. Then, without warning, I launched at it.

Kicking. Punching. Hitting it over and over until my fists bled.

I remember being carried away, my mother lowering me into a cold bath to calm me down.

And then, as I rose out of the freezing water, I screamed until I lost my voice.

My mother, she held me.

Until I had no other option than to surrender to the pain.

—So, this is why I feel dread around my birthday. It’s probably not the happy ending you were hoping for, but my life has been a series of unfortunate events that eventually turned around. Although this is how I feel around my birthday, I do have people who love me and celebrate me—even through my moodiness on this day. Two things can exist at once—my dread for my birthday and my gratitude.

Life isn’t always perfect or filled with happy endings. And I’m okay with the cards life handed me.

My story is not all dark. I did have magical and wonderful moments woven in with the hardship, and I will share those as well. Today, I have a beautiful little life. I have the career of my dreams as a writer and author. My children have filled me with more love than I was ever robbed of. My husband—15 years strong together, my protector. I have a community bigger than I ever imagined, one that supports and loves my work, my books, my decks, and my writing. And that celebrate me.

On my 44th birthday, I just want to say thank you for being a good part of my life story.

I appreciate you like crazy.

buy me a coffee: https://buymeacoffee.com/iamjulietdiaz

Consider becoming a paid subscriber

By choosing this option, it allows me to continue my work in activism, community care, and my writing.

What You’ll Receive: You get all of the free benefits +

• virtual gatherings + paid subscriber posts & archive access

• access to the seasonal spiritual alignment series - learn more HERE

• exclusive practices (journal prompts, rituals, spells, breathwork, meditations, & more)

• access my community chat room (access the chat through the substack website or app)

Join a safe and inclusive space where I share behind-the-scenes, insights, and thoughtful notes. A weekly oracle reading + giveaways. This is the only community space I have where we can interact, share, and connect more intimately.

My website (signed books, workshops, courses, services, merch) - www.iamjulietdiaz.com

PRE-ORDER my forthcoming book: THE ALTAR WITHIN - A Devotional Guide To Liberation (2nd Edition) —Pre-Order HERE

"Never trust the oppressor. They will eat your mind and claim your soul". I read that and I felt such fire in my heart. For you for your mom for us all. I have my baby's first birthday this weekend. He's the first Pisces in my life and when you wrote that your babies gave you all the love you were robbed I looked at him and I feel that too.

Thank you for sharing this beautiful tribute to yourself, your parents, your community, your growth. Really beautiful.